(845) 246-6944 ·

info@ArtTimesJournal.com

Audrey

Dick Kessler at Café Mezzaluna Bistro Latino and Gallery

By

RAYMOND J. STEINER

|

Curated

by Mery Rosado, proprietress of Café Mezzaluna Bistro Latino and director

of the Café’s gallery, this is not the first exhibition Rosado has hosted

— the Café is well known in the area for both its regular support

of both art and live music — but it is the first that she has

mounted without benefit of accompanying information about the artist.

Audrey Dick Kessler, it appears, is somewhat of an unknown entity. What

is definitely known is that she had lived in Woodstock, New York, that

she studied under a number of teachers at the Woodstock School of Art,

that she had lived for a period of time in the Bahamas, and that she

has recently died of a serious illness while still in her early 60’s.

As best as can be determined, this is the first public exhibition of

her work.

|

At

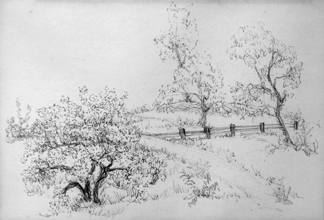

even a cursory glance, what is readily apparent is that Kessler was

not only talented but gifted as well. Looking first at her drawings

(there are about a dozen) — for me, always the best indicator

of an artist’s innate technical abilities — we find a skillful

coordination between eye and hand, her application of either ink, crayon,

or charcoal both sure and accurate. One of my favorites — a small

landscape depicting a field bisected both by a parallel (to the picture

frame) wooden fence and by a diagonal path that cuts from the right

foreground to disappear into the left background — has three trees

dominating the space — all objects sensitively observed, meticulously

drawn, and finely detailed. However, most of her drawings are of figures

— some simple pencil sketches of reclining male and female nudes

and others, formal upper torso figure studies (classroom exercises that

were once known as “academics”), which are also of both sexes. The larger,

more formal, studies are extremely accomplished, most indicating that

the depiction of the human form was not only her forte (the exhibit

is comprised of a selection of figures, landscapes, and still lifes),

but also her preferred subject matter. Both sexes are handled with a

cultivated eye; yet, to this viewer, it is in her handling of women

that Kessler reveals the full depth of her perception into the human

psyche.

|

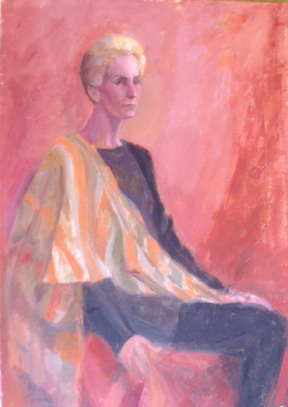

Especially

fine are her renditions (paintings as well as drawings) of older women.

Here the artist delves beneath the surface beauty of form to uncover

the full psychology that lies behind the visage. On the strength of

these alone — and there are only a handful of these studies of

mature females — one would feel justified in characterizing Kessler

as an accomplished artist abundantly aware of the human condition —

in short, not merely a skilled figure painter, but also a soulful humanist

well aware of the tenuousness of life.

Her

still lifes — two florals and a rather large and “busy” rendition

of a cloth-covered wooden table laden with a vase, ceramic pot, cutting

utensils, several pumpkins and what could be either a sombrero or a

napkin heaped in a cone-like shape — do not fare well alongside

her figure and landscape studies. To my eye, they seem somewhat inert,

classroom exercises that appear to be executed in a rather mechanical

manner — as if done to please an instructor rather than to explore

her own aesthetic vision.

Though

I am persuaded that it was the human form which most occupied Kessler’s

creative interest, I was equally impressed by her handling of landscape.

If it was to the human condition that her heart and mind were drawn,

I have little doubt that the lure of the natural world also carved its

own place in her soul. A large landscape in oil — a gnarled tree

standing before four distinct planes of color (green, gold, green, brown,

respectively) with snatches of the sky glimpsed through its tightly-leaved

and green-drenched branches — is compelling in both its composition

and in its impact on the eye. Perhaps because it is “local” in feeling

— namely, what appears to be a typical “Woodstock Scene”, this

painting (as well as some of the small landscape drawings) is more authoritative

than the two watercolors that are most likely Bahamian scenes —

tropical locales that seem not to have penetrated her consciousness

as deeply as have Woodstock’s natural surroundings.

|

Aside

from individual works, one is struck by Kessler’s range — not

only in terms of size, mediums, color handling, and motifs — but

one must also admit, in degrees of technical expertise. Of course, we

have no means of knowing which of these works were considered as “finished”

— if indeed, any of them were ever intended to be put on public

view. The fact remains, however, that several seem to be “works-in-progress”,

little more than exploratory forays at “getting one’s ideas down” before

they flit away into oblivion. Several are monochromatic and/or monolithic;

others a medley of Matissean color and texture — as if the artist

has still to decide what each completed work was destined to look like.

Others seem to be applied in a hurried fashion — as if the artist

knew how limited her time was and how important it was to get a statement

— some statement — down on canvas before it was too

late or, perhaps, was just an attempt to get at essence before it “gelled”

too quickly into form. One is left with the feeling that it is precisely

the artist’s knowledge of her own mortality that lies behind not only

what comes across as haste, but also compelled her to jump from instructor

to instructor, as if her need to determine her vision, her

intent, her expression, necessitated

not being ensnared by anyone “other.” Whether or not we can leap so

far into conjecture, it seems to me almost certain that her consciousness

of her pending death acutely sensitized and shaped the underlying humanism

common in her figural work.

I

applaud Mery Rosado for her willingness to give over her gallery space

to an artist that is “unknown” in much more than our usual understanding

of that term — it most surely underlines her genuine wish to support

the arts. This is a show that deserves a visit — edifying and

visually pleasing on more than one level. In a sense, it reveals the

artist herself as a “work-in-progress”, allowing us a glimpse —

if not into her mind — at least into a facsimile of her working

studio.

You

won’t be disappointed — and, while you’re there satisfying your

visual appetite, tempt yourself further by glancing at Mezzaluna’s gustatory

Latino delights — the food won’t disappoint either.

“Audrey

Dick Kessler” (thru Jul 14): Café Mezzaluna Bistro Latino and Gallery,

626 Rte 212, Saugerties, NY (845) 246-5306